Coal Ash

Coal ash is a waste product of coal-fired power plants that contains arsenic, cadmium, lead and mercury among other toxins. When stored improperly in unlined landfills, coal ash can cause pollution by leaching, or draining, heavy metals into nearby waterways. Many of these metals are carcinogens (capable of causing cancer) that may cause significant health risks for people exposed through drinking water or through recreation in contaminated areas.

Like many power plants that use heat to make electricity, coal plants are often built near rivers to provide easy access to water for cooling. For decades, the Environmental Protection Agency failed to set requirements for safe coal ash disposal, leaving coal ash to pile up in unlined ponds and landfills near vulnerable rivers that provide clean drinking water for neighboring communities.

Federal Rules Trigger Coal Ash Pond Closures

Two major spills in Tennessee and North Carolina brought national attention to the need for federal standards for coal ash disposal. In 2008, 1.1 billion gallons of slurry escaped the Kingston Fossil Plant when an earthen retaining wall collapsed, sending contaminated water and mud over hundreds of acres of rural lands. Even closer to home, a 2014 spill at Duke Energy’s Dan River Steam Station released 39,000 tons of ash and 27 million gallons of polluted water into the Dan River before a broken storm drain was finally repaired a week later.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released a long awaited federal rule in 2015 setting the nation’s minimum standards for disposing of coal ash. Together with the Clean Water Act, this rule creates a two-part process for Virginia utilities closing coal ash ponds: dewatering and final closure.

Dewatering: Coal ash ponds contain a slurry of water and ash that prevents the ash from blowing off-site while the pond is in use. Before closing a pond, the utility must get a Clean Water Act permit approving its plan for draining and treating the water before ultimately releasing it into the environment.

Final Closure: Under the 2015 EPA rule, coal ash is considered solid waste, and utilities need a Virginia solid waste permit to show their disposal plan and landfill meet state and federal laws. This includes specific technical requirements on location, design, and groundwater monitoring.

- Virginia lawmakers strike deal to remove coal ash from ponds next to rivers – January 2019

- PRESS STATEMENT: General Assembly Takes Action to Protect Virginia’s Rivers from Coal Ash – January 2019

- 2019 General Assembly begins today – January 2019

- General Assembly Hot Topic: Coal Ash – February 2018

- 2018 General Assembly Wrap Up– March 2018

- 2018 General Assembly is in session– January 2018

- James River Association Responds to Coal Ash Assessments– December 2017

- JRA applauds Governor McAuliffe for signing Coal Ash Bill – May 2017

- Coal Ash Bill Passes General Assembly! – April 2017

- James River Association applauds Governor McAuliffe for amendments to Coal Ash Bill And placing a hold on Coal Ash Pond Permits – March 2017

- Tell Legislators: Protect Our Waters from Coal Ash Toxins – February 2017

- ACT NOW – Protect Our Waters from Coal Ash Toxins – February 2017

- Coal ash leaks, toxins, uncovered through water quality monitoring – January 2017

- James River Association settles with Dominion over Bremo coal ash ponds

In the James River Watershed

Dominion Energy has a total of 21 million tons of coal stored in unlined ponds at two power plants located on the banks of the James River: Bremo and Chesterfield.

Bremo Power Station

Located in Fluvanna County, 60 miles upstream of Richmond, the Bremo station burned coal from 1931 to 2014. All of Bremo’s boilers are now dormant in “cold reserve” status.

Dominion currently has 6.2 million tons of coal ash stored in three unlined ponds at this location. Under legislation recently passed by the Virginia General Assembly, all of the coal ash will be excavated and either recycled or placed in a lined landfill.

Chesterfield Power Station

The Chesterfield Power Station, 13 miles upstream of Hopewell’s drinking water intake, began burning coal in 1944. It currently has two retired coal boilers and two more in reserve.

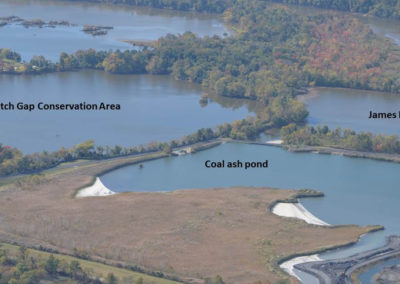

Dominion’s two unlined coal ash ponds at this facility are just on the border of Chesterfield County’s popular Dutch Gap Conservation Area and hold almost 15 million tons of ash. Under legislation recently passed by the Virginia General Assembly, the coal ash will be excavated and either recycled or placed in a lined landfill.

EPA’s standards for new coal ash landfills require liners and also require that these landfills be placed in locations that would not impact groundwater or surface water. Importantly, the landfills at both of Dominion’s facilities along the James would not meet EPA’s standards for new coal ash landfills. Dominion’s groundwater monitoring over many years has shown contamination from leaking coal ash ponds at both of these facilities. Surface water sampling completed by the James River Association has identified additional seeps from Chesterfield Power Station’s coal ash ponds, where arsenic levels in soil measured 400 times the level considered safe, according to EPA risk assessment criteria.

Communities near Bremo and Chesterfield would continue to be at risk of contamination from heavy metals and other toxins without a requirement that the utility recycle the ash or move it into safer, lined landfills.

Moving Virginia Ahead to Safely Close Coal Ash Ponds

Together with our partners and the help of our Action Network, we’re working to keep Virginia communities safe by calling on Dominion to safely dispose of coal ash through beneficial recycling and safe removal to lined landfills. Here’s where things stand:

In 2017, the Virginia General Assembly passed Senate Bill 1398, which responded to public concerns over coal ash pollution by putting a hold on closure permits. The bill required detailed assessments of coal ash ponds to identify existing pollution issues and to evaluate closure options for long-term safety and protection of natural resources. The report acknowledged groundwater contamination at these facilities, but lacked thorough plans to address existing pollution issues or long-term risks like stronger storms, more frequent flooding, and rising sea levels.

During the 2018 General Assembly, JRA worked successfully with partners to pass Senate Bill 807, which extended the moratorium on closure permits for another year. The legislation required Dominion Energy to fully evaluate recycling options for all of their legacy ash statewide by soliciting bids from businesses through a request for proposals (RFP) process. On November 14th, Dominion released a report summarizing the RFP bids. The report confirms that there are multiple strategies for transporting and recycling much of the legacy coal ash at all locations and landfilling the rest within the next 15 years. In November 2018, Dominion released a report summarizing the RFP bids, and describing costs and strategies for beneficially reusing coal ash.

In the 2019 General Assembly session, JRA worked with the Administration, environmental and industry stakeholders, as well as a bipartisan group of state lawmakers to pass legislation that calls for the full removal of all coal ash from leaking ponds across the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Under this clean closure agreement, at least 25% of the coal ash will be recycled into much-needed encapsulated products like concrete, while the remaining ash will be excavated and placed in modern lined and monitored landfills.

Unchecked coal ash pollution from unlined ponds is a risk to the James, to our parks, and to our drinking water. As Virginia’s leaders examine the options for coal ash disposal, we encourage them to make pollution prevention a priority, and to keep heavy metals and toxins from reaching our waterways.

Here are a few other resources:

- HB2786 – Clean Closure Agreement

- Coal Combustion Residuals Recycling/Beneficial Use Assessment Business Plan – Dominion Energy Virginia

- Aquilogic Review of Chesterfield Groundwater Conditions

- Aquilogic Review of Bremo Groundwater Conditions

- Coal Ash in Virginia: Achieving Safe and Responsible Closure of Coal Ash Ponds